Duke University’s Centennial Oral Histories Program includes one-hour videotaped interviews with former and current leaders of Duke University and Duke Health, during which they share memories of their time at Duke and their hopes for Duke’s future. The videos will be archived in Duke’s Archives as a permanent record and enduring legacy from Duke’s 100th anniversary. Subscribe to the podcast to watch or listen to the interviews as they are released.

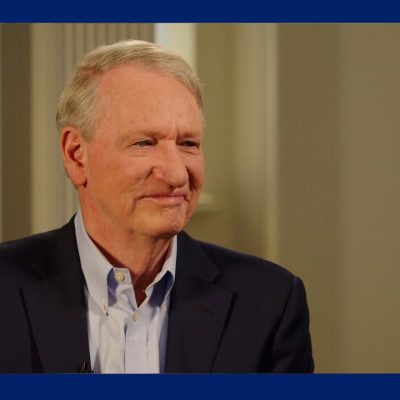

Currently serving as commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Robert Califf is a Duke alumnus and renowned cardiologist who has held prominent leadership roles at Duke including founding director of the Duke Clinical Research Institute. In this interview with Dr. Adrian Hernandez, Vice Dean and Executive Director of the Duke Clinical Research Institute, Dr. Califf talks about his life, his mentors, and the emergence of data-drive research.

Robert (Rob) Califf ’73, MD ’78

- Commissioner of Food and Drugs (2016-2017; 2022-present)

Interviewed by

Adrian Hernandez, MD

- Duke University Board of Trustees (2014-2026)

- President, Duke Alumni Association Board of Directors (2008-2010)

September 27, 2024 · 10:00 a.m.

President’s Lounge, Forlines Building, Duke University

00:00:19:06 – 00:00:43:06

Adrian Hernandez

Hi, I’m Adrian Hernandez. I want to welcome you to Duke’s [Centennial] Oral History [Program]. I’m here with [Robert] Rob Califf, who spent a number of years at Duke. And, we’re going to have a conversation about his time before Duke, during Duke, and what he’s doing now, and looking into the future. So, Rob, let me start off, first, to hear a little bit about your background.

00:00:43:08 – 00:00:50:06

Adrian Hernandez

You were born in South Carolina. What was that like? Or were there any influences [there] later in life?

00:00:50:08 – 00:01:11:10

Rob Califf

I think we’re all heavily influenced by our youth. And in my case, my dad was an architect, and he was teaching at Clemson [University] when I was born. So at heart, I’m actually a Clemson guy. But when I was five, we moved to Columbia, the capital of South Carolina, and he was very involved in designing buildings there.

00:01:11:10 – 00:01:48:23

Rob Califf

My mom was a schoolteacher. [It was] a very, I would say intellectual [and] academically-inclined family, with dinner table conversations about politics and the direction of things. And of course that time, the early-to-late 1950s, was sort of a stable time as I think of it in American history. But then the 1960s [were] a very tumultuous time and particularly shaping me was this integration that was happening in the South.

00:01:48:23 – 00:02:03:02

Rob Califf

And I think a lot of people who are younger don’t even realize how recent that was. I started out in totally segregated schools, and it was during my high school years that integration occurred.

00:02:03:04 – 00:02:17:06

Adrian Hernandez

And during that time, as you were in high school, were there things then that made you interested in pursuing healthcare or research later? How did that come about?

00:02:17:08 – 00:02:44:08

Rob Califf

When I was in high school, I was mostly interested in basketball. I ended up being captain of the state championship basketball team for South Carolina. Probably the pinnacle of my career in anything [was] the day after [I] won the state championship. That night, you’re on top of the world. Then you recede back into normal life. It’s kind of deflating. But I also would say I had a very political period then.

00:02:44:08 – 00:03:08:08

Rob Califf

It turned out, one of my friends through school, all the way, was Lee Atwater, who was the famous Republican strategist. I was on the other side of the fence. We were arguing even back in junior high and high school. But I really didn’t have designs on medicine or healthcare. It is noticeable that during that period of time,

00:03:08:08 – 00:03:24:18

Rob Califf

every year you took an aptitude test for what you should do with your life. And they kept saying I should be a doctor. And I mostly rejected that idea. It was only later, my junior year at Duke, that I switched to Pre-Med.

00:03:24:20 – 00:03:47:02

Adrian Hernandez

Right. Well, interesting. I imagine some of the things that you’re dealing with in terms of political science actually came together later in life. Now, going to the basketball team, I imagine touring around the state and playing other teams during that time was probably pretty interesting, especially this era where there was integration and playing different teams.

00:03:47:04 – 00:04:09:08

Rob Califf

It was a fascinating time. There was a rule in South Carolina that the coach couldn’t coach the team during the summer. And so as captain, I was actually sort of the proxy coach. And one thing that we did, I still have vivid memories of this. We had Black players on our team, but there were still all Black high schools.

00:04:09:08 – 00:04:37:13

Rob Califf

So we toured the all Black high schools and scrimmaged them, which was a spectacle. The crowds were — it was a full packed gymnasium every time, with cheers that I had never heard growing up in the other schools that were a little bit disconcerting. But that toughened us up quite a bit. And I think it was part of the story of how we ended up eventually winning the state championship.

00:04:37:15 – 00:04:45:18

Adrian Hernandez

Well, that’s pretty awesome. And was there any idea about either playing at Duke, or being recruited to Duke for basketball?

00:04:45:19 – 00:05:18:20

Rob Califf

I had brief dreams of a college career, and I got some letters from, I would say, the lower-ranked schools, not the 1A schools. Also in 1968 [and] 1969 the assassinations had occurred, the Vietnam War was going strong. And at that point, I really sort of lost the intense focus on staying in shape and playing sports.

00:05:18:20 – 00:05:26:10

Rob Califf

Although I did play a lot of intramural basketball at Duke, and I switched to other interests at that point.

00:05:26:12 – 00:05:33:17

Adrian Hernandez

So you showed up to Duke in the late 1960s. What led you to Duke? How did you choose Duke?

00:05:33:22 – 00:05:57:09

Rob Califf

Well, my older brother had come to Duke, and he was a couple of years ahead of me. And when I came to Duke, it literally was the furthest north I had been in my life. You know, travel was different then. And I never really had hardly been to North Carolina for anything, other than up in the mountains occasionally when we lived in Clemson.

00:05:57:09 – 00:06:24:10

Rob Califf

So it was actually a big journey for me to come to Duke. And quite startling to walk into House L, the freshman dorm, with all these people from all over the country. It was an amazing experience. So the draw was really good academics and good sports, and kind of like the way it is now when I look at undergrads.

00:06:24:12 – 00:06:30:13

Adrian Hernandez

And during that time, what was it like with your fellow students?

00:06:30:15 – 00:06:59:10

Rob Califf

Well, I just remember it being intense, and we made a lot of friends. And in fact, last year we had our 50th Duke reunion. And although we had gone all over the country, in different parts of the world, doing very different things, it was as if we were back together again 50 years later. Still able to relate to each other very easily and just having amazing conversations.

00:06:59:12 – 00:07:21:17

Rob Califf

But the other part of it was, it was such a tumultuous time. In the history of the University, too. The year before had been the takeover of the Allen Building. The year before I came. Integration on the campus was a big deal. Not so much the students, as I remember it, but the workers in the hospital. It was a huge deal.

00:07:21:19 – 00:07:42:16

Rob Califf

But we didn’t have classes most of the second semester because of the Vietnam War. And although I spend a lot of time in Washington now, my first visit to Washington was on a bus where I got tear-gassed. I take the Red Line [transit line] in Washington now, from my apartment building to the HHS offices next to the Capitol.

00:07:42:16 – 00:08:07:21

Rob Califf

And every time I go through DuPont Circle, I have a brief recollection of running into the basement of a church at DuPont Circle, having been tear-gassed. So the absence of classes was a remarkable period, I think, in the University’s history. But things held together, and became more regularized as all that worked out.

00:08:07:23 – 00:08:19:15

Adrian Hernandez

Now, it’s pretty amazing to go to your 50th anniversary. And I imagine most people didn’t go into medicine like you did, or the types of careers that people went into.

00:08:19:17 – 00:08:48:04

Rob Califf

Gosh, we had city administrators, dentists, people who wrote for newspapers or [wrote] books, engineers. It was really an eclectic mix from all over the country, and just about every profession that you can imagine. But we still had so many things in common, and [it was] easy to hang out together and chat.

00:08:48:04 – 00:09:02:10

Adrian Hernandez

You eventually graduated with a major in psychology, which is kind of interesting, seeing the role that you have now dealing with a lot of people and a lot of different organizations. How did you pick that?

00:09:02:12 – 00:09:26:07

Rob Califf

Well, I developed a deep interest in psychology, actually back in high school, and was very focused on it. I was going to be a clinical psychologist, and I ended up working in the South Carolina state prisons for two summers, which was a tremendous experience. But I sort of concluded after that first summer that maybe I wanted to do something that was a little bit more tangible.

00:09:26:07 – 00:09:58:22

Rob Califf

It was tough to be — it turned out some of my high school competitors are now inmates in the prison. And I got to see how difficult it was to exert change. So I’ve always had a lot of respect for people who work in the mental health field ever since then. But it sort of hit me that, maybe for me, I should do something that had a little more concrete [application], where you might see a problem and could help fix it. And medicine,

00:09:59:00 – 00:10:29:14

Rob Califf

ultimately cardiology, really fits the bill. When you see someone in ventricular fibrillation and you apply some Duke power and defibrillate that person from being dead to being alive, that’s pretty concrete. So that was a big switch. I had taken no science courses until basically finishing my junior year. So after graduating from Duke, I took a year off and worked as an orderly, because I had crammed all those science courses . . .

00:10:29:15 – 00:10:31:09

Adrian Hernandez

At Duke Hospital?

00:10:31:15 – 00:11:04:02

Rob Califf

No, I was over in Greensboro. Got married. [My now-wife] Lydia [Califf] was in school at UNC-Greensboro. And that was an amazing experience [crosstalk, laughter]. Well, the whole thing of marriage has been amazing. 1973 to 2024, we’ve had a long and great marriage. But serving the needs of people at a basic level is humbling.

00:11:04:03 – 00:11:13:20

Rob Califf

It also, I think, teaches you a lot of things that I worry a lot of medical students never think about until they may be too far along.

00:11:14:00 – 00:11:32:23

Adrian Hernandez

We’ll talk about that theme, about caring about the front line. It sounds like you had some of that direct experience that’s continued on. So you went on and decided to go into medicine. You chose Duke Medical School. Was that an easy choice? How did you get there?

00:11:33:01 – 00:12:02:02

Rob Califf

Well actually, it was surprising. I thought I was saying goodbye to Durham. And, you know, you mentioned Washington. This came up last night. I can’t quite get over it. But one of the fellow awardees with me at the Founders’ Day celebration last night is an animal behavior expert who had mentioned that there was a goat colony that Duke kept up for people to study animal behavior.

00:12:02:02 – 00:12:14:06

Rob Califf

And I actually did that for a semester, studying the hierarchical behavior of goats. It turns out that has been a fabulous background for dealing with Washington politicians. Very similar.

00:12:14:08 – 00:12:15:13

Adrian Hernandez

Behavioral economics, quite interesting.

00:12:15:13 – 00:12:31:14

Rob Califf

There’s a hierarchy, and the goats know exactly which goat gets dominance over the others in different situations. And I think the same thing — it’s pretty obvious in politics that it works that way.

00:12:31:14 – 00:12:38:14

Adrian Hernandez

Right. And so, when you went to Duke Med School, what was that like?

00:12:38:14 – 00:13:03:16

Rob Califf

So, I was not expecting to come back to Durham. And I’d actually paid the down payment at Tulane [University] when the Duke admission came through. And it was a hard decision. Tulane would have been great, but it ultimately, I think, worked out really well for us. You know, we didn’t have a lot of money.

00:13:03:16 – 00:13:25:06

Rob Califf

Well, we had a very meager subsistence, but Lydia was working as a nurse at Duke Hospital. She had gotten her nursing degree at UNC-Greensboro, and it was just a fabulous culture and experience. But, my first day we went to a medical grand rounds and got to see [Duke’s] Dr. Eugene Stead in action.

00:13:25:06 – 00:14:05:21

Rob Califf

A neurologist was presenting a case and halfway through it, Dr. Stead got up and basically told the neurologist, “You’re wrong.” They got into an argument. And it was quite an introduction to the complexity and personalities in medicine. But what a bond that first year at Duke. Early on, Duke took this position to compress the basic sciences into one year. Very intense. And so you talk about friends and relationships, that first year class was remarkable and still something I think about a lot.

00:14:05:21 – 00:14:17:04

Rob Califf

And then that second year you’re out there taking care of patients. An amazing experience in the old Duke hospital. Learned so much.

00:14:17:13 – 00:14:27:00

Adrian Hernandez

So when did you get exposed to research? You said some in undergraduate time. But medical research, when was that?

00:14:27:02 – 00:14:52:09

Rob Califf

Yeah, I would say most of my undergraduate research was some observations and a little bit of writing, not heavy-duty research. But I needed to work part-time while I was a medical student to help pay the bills. And I end up working with this new thing called a computerized database that had been developed, actually by Dr. Stead.

00:14:52:11 – 00:15:19:14

Rob Califf

And it was amazing to me because at the time all medical communication, as you know, was handwritten. Including the orders for the patients [and] the clinic notes. Essentially everything was handwritten. And so doctors got to be well-known, basically by having good memories, or being able to concoct stories about their memories that were believable to other people.

00:15:19:16 – 00:15:44:21

Rob Califf

But it turned out when you had computerized data, very simple things that we take for granted today — you could say that a lot of the recollections and beliefs of the doctors – were just flat-out wrong. And the ability to aggregate information over time, it was just — Dr. Stead was way ahead of his time, as he was in some other things.

00:15:44:23 – 00:16:18:22

Rob Califf

In this regard, he not only realized that capturing information in computers was important, but the longitudinal nature of the disease and outcomes [was also]. His rule that he put into place was [that] once you got entered into the database, you were followed for life. And there’s so many cognitive tricks that we know about now but people still fall prey to them. Like how someone looks initially after a treatment is instantiated into your mind as that’s how the treatment works.

00:16:19:00 – 00:16:39:07

Rob Califf

But there are many treatments that either have no effect early, or even a detrimental effect early, that show later benefit. And of course at the time, coronary bypass surgery was brand new. So he would take me to conferences, because every case was reviewed, and the cardiologists and surgeons would look at the old cinifilms.

00:16:39:08 – 00:16:40:07

Adrian Hernandez

This is when you were a med student?

00:16:40:12 – 00:16:50:08

Rob Califf

When I was a med student. And he would say, “They’re going to say X, Y, and Z, but here’s the computerized data and they’re making the wrong decision.”

00:16:50:11 – 00:16:52:12

Adrian Hernandez

Really. What year was this?

00:16:52:12 – 00:16:53:11

Rob Califf

This is..

00:16:53:13 – 00:16:53:20

Adrian Hernandez

What years?

00:16:54:00 – 00:16:57:05

Rob Califf

1976, 1977.

00:16:57:05 – 00:16:59:00

Adrian Hernandez

Wow. Okay.

00:16:59:02 – 00:17:19:06

Rob Califf

And so to this day in my job at FDA, I still see so many situations where common sense beliefs by doctors and patients and other practitioners don’t fit with what the data actually show. And it’s a lesson I think we have to learn over and over.

00:17:19:08 – 00:17:26:06

Adrian Hernandez

Now, give us a sense of what you mean by computer. Like it. It’s not just, say, a laptop or something.

00:17:26:10 – 00:17:48:10

Rob Califf

No, we had a thing called a PDP-11 that took up an entire room in Duke South. And you would enter your code, and for most things we did, you would come back the next day. It would run all night, and then you would get your answer to the question. This, of course, was a more genteel time of academic medicine.

00:17:48:12 – 00:18:11:11

Rob Califf

I was a student and I was working with all the cardiology fellows and they had a team — it was a unique thing at the time — but a multidisciplinary team. One of the original biostatisticians, Kerry Lee. One of the original engineers who worked with software, Frank Starmer. And one who sort of bridged it, Ed Hammond. Ed, of course, is still around.

00:18:11:13 – 00:18:53:12

Rob Califf

The team built new things and broke a lot of ground. This was a tremendous education for me, because I went with them to some NIH site visits where their pioneering work was not very well-received. It was considered avant garde and upstart. And in fact, one of the most important things Dr. Stead did, which you could never do now, is he took a grant that was given for physiologic monitoring — again, hard for young people to believe, but we were just beginning to put rhythm monitors on people in intensive care units.

00:18:53:14 – 00:19:17:08

Rob Califf

But he took the money and built this database to measure patient outcomes over time. They did reverse site visits at the time. He totally shocked the site visitors. “You gave me the money for this, but here’s what I did with it.” They were not too happy. But at the time you could get away with that. And the kind of creativity that was shown in this group just — I was sold. I mean, there was no way I was going back.

00:19:17:08 – 00:19:24:15

Adrian Hernandez

What a special time. I mean, almost 50 years ago, to think about something that now we take for granted — computerized medicine.

00:19:24:17 – 00:19:47:09

Rob Califf

There’s another thing that happened [which was] that the death rates at the time, coronary care units were filled with 50-to-60 year old people, mostly men who were cigarette smokers. And they died at alarming rates. And the Holter monitor had just come out, speaking of monitoring. So my project as a student was to put Holter monitors on people.

00:19:47:09 – 00:20:11:07

Rob Califf

I only needed 386 people, and then [I] followed them while I was still a student, like for a year. So many people died that we had very meaningful outcome data. And the question was, could we predict sudden death? And it turned out, the hypothesis was that the arrhythmias shown on this new Holter monitor would be the best predictor.

00:20:11:09 – 00:20:34:19

Rob Califf

And I put the data together and brought it to Kerry Lee, the statistician. He ran some regression analyses. And lo and behold, it wasn’t the cardiac arrhythmias. It was the underlying left ventricular function. So we brought that up, and it was not a popular message. It was not well-received. People didn’t believe it.

00:20:34:21 – 00:21:02:18

Rob Califf

And I went on out to UCSF for my internship. But our abstract was accepted to the American Heart Association in Miami. And it was one of those things where I just barely got a couple days off [and] got on the plane. At the time we had the slide carousels with our slides. I ran into the Fontainebleau Hotel, gave my talk, and the commentators just basically said I was stupid and I had gotten it wrong.

00:21:02:19 – 00:21:14:22

Rob Califf

But the conclusion of our study was that treating sudden death [was] going to be a matter of identifying people with impaired left ventricular function. Guess what?

00:21:14:22 – 00:21:16:04

Speaker 4

We were right.

00:21:16:06 – 00:21:20:06

Rob Califf

So what’s the criteria now for a defibrillator? It’s LV function.

00:21:20:08 – 00:21:36:21

Adrian Hernandez

So that’s a really interesting insight. Just shows the power of data and making sure to eliminate, as much as possible, biases. So you spent time in the Bay Area. You eventually get back there. What was that like during a residency at UCSF?

00:21:36:23 – 00:22:03:18

Rob Califf

I loved it. There was an event that happened. Our first child was born, just as I was finishing that fourth year of medical school. And it turned out she had really serious congenital heart disease. But it was actually not diagnosed at Duke, even though she was not thriving. So we traveled across the country not knowing why our baby was not growing at a normal rate.

00:22:03:20 – 00:22:25:09

Rob Califf

And for people that have been to San Francisco in the summer, you’ll relate to this story. But we arrived in June, started the internship, I took Sharon out on the porch on a July day when the fog was in. It was like 45 degrees in July. And she turned blue, right in my arms.

00:22:25:09 – 00:22:47:01

Rob Califf

And she ended up having a huge operation while I was an intern. So we would make rounds on all the adult patients while I was a medical intern. We would go around on my daughter in the ICU. That was a month of my internship. But, you know, it’s amazing. The people everywhere are pretty much the same. They took really good care of us.

00:22:47:03 – 00:23:11:20

Rob Califf

We made friends for life. And I know you spent time there, too. So you have a sense of the community there. I fell in love with San Francisco. And it actually turns out San Francisco and Durham, in my opinion, have a lot in common. They’re very heterogeneous towns. And the people in San Francisco tend to be really friendly and easy to talk with.

00:23:11:21 – 00:23:27:07

Rob Califf

Much like the people in Durham. It doesn’t matter what your background or skin color is, you pretty much get along with everybody. I find Durham to be similar, and increasingly so, as a melting pot community.

00:23:27:09 – 00:23:49:07

Adrian Hernandez

And I also think of the sense of collaboration at the university. Same thing in both places. Now, you came back to Duke for cardiology. I assume there were some things here that you still wanted to continue to pursue when you came back for cardiology?

00:23:49:09 – 00:24:16:16

Rob Califf

Yeah, that was actually a really hard decision. You know, those were the days of short-tracking in medicine. So I had done two years [and] had conversations about being a chief resident, which is a very prestigious thing at a place like UCSF. But I was addicted to the computer. And now you would never believe it, but the Bay Area was way behind in computing.

00:24:16:16 – 00:24:34:11

Rob Califf

Duke was way ahead. And in addition, Sharon was still — you know, we’d been through quite a traumatic thing, and we wanted to be closer to family. So we came back, and I went right to work as a fellow and had a fabulous time.

00:24:34:13 – 00:24:51:14

Adrian Hernandez

And then you came on the faculty shortly after that. What was that time like? 80% protected time for research and occasionally [you’d] see patients?

00:24:51:15 – 00:25:08:06

Rob Califf

Once again, two years into the fellowship, the Coronary Care Unit director, Eric Conn, went into practice in Chattanooga. And Joe Greenfield, the chief [of Cardiology], called me in and he said, “I think we need you to be the attending on the Coronary Care Unit while you finish your fellowship.”

00:25:08:08 – 00:25:09:08

Speaker 4

So,

00:25:09:10 – 00:25:27:21

Rob Califf

somehow that was managed. And that’s actually what I did. I was on call for both Duke and what [is now Duke] Regional Hospital. It was Watts Hospital or Durham County at the time. So I was on call 12 out of 14 nights. That first year when I took over the..

00:25:28:02 – 00:25:31:06

Adrian Hernandez

12 out of 14?

00:25:31:11 – 00:25:56:03

Rob Califf

Yeah. The first year was that time when the first coronary angiograms were done showing that what caused heart attacks was a blood clot. Hard to believe that I was taught as a medical student that blood clots did not cause heart attacks. It took some adventurous cardiologists doing acute angiograms to see that. But then the race was on.

00:25:56:03 – 00:26:15:03

Rob Califf

What do you do about it now? You know, the leading cause of death. I was losing 4 or 5 people a day on the Duke Coronary Care Unit, because we essentially had no treatment. And dissolving the blood clot was something that we knew could be done. So that set off a race.

00:26:15:03 – 00:26:36:06

Rob Califf

So, the 12 out of 14 nights were literally very often coming in to see a chronically ill person and put them on a protocol. And very few other institutions were doing this kind of work. So it was very high-stakes and high-profile.

00:26:36:08 – 00:26:40:13

Adrian Hernandez

And so [those were] some of your first clinical trials?

00:26:40:14 – 00:27:16:23

Rob Califf

Right. What happened was Eric Topol, who is known by a lot of people now, was one of my interns at UCSF. And he went to [Johns] Hopkins to do his cardiology fellowship. And we essentially formed a little study group of former UCSF residents and interns. [It was] Dean Kereiakes who’s now in Cincinnati, Barry George, and Dick Candela in Columbus. And we would literally treat an acute patient, do our work in the cath lab,

00:27:16:23 – 00:27:41:22

Rob Califf

and then we would get on a plane and look at the films together and try to figure out what to do next. But then what happened was this was such a big problem, and so high profile, [that] the pharmaceutical industry realized that this was an opportunity to save lives. And so there were an endless series of efforts to develop effective drugs and devices to treat this problem.

00:27:42:00 – 00:27:51:07

Rob Califf

So because we had the computers at Duke, we became the coordinating center for these efforts. We had the data.

00:27:51:09 – 00:28:08:12

Adrian Hernandez

So it sounds like that continued on [to the] next phase of what was called the Duke Databank. So when did you transition from just watching people through the databank to actually doing randomized trials?

00:28:08:14 – 00:28:41:20

Rob Califf

Well, I want to say, again, I give a lot of credit to Dr. Stead and the many people around him — [Robert] Bob Rosati [and] Galen Wagner were part of the group. Frank Harrell came on as a junior statistician — who has been a luminary [in] all this, as far as I’m concerned. But what Dr. Stead and team realized was that the best way to practice medicine was to use the human skills but depend heavily on the computer to support the human skills. To give you the information that you needed to work with patients to make the best decisions.

00:28:41:21 – 00:29:08:02

Rob Califf

That led to a whole analytical scheme of observing, recording information, analyzing the data. What we now call observational treatment comparisons. But it quickly became apparent to me that it was very hard to get the right answer. Because one issue was the time dimension that we talked about. What looks better early on, might not look so good later on, and vice versa.

00:29:08:04 – 00:29:36:05

Rob Califf

But also, the reasons why people got one treatment or another are based on reasons that could not be quantified. And so, as we started to do some randomized trials, I [started] to realize that if you want to get the right answer about therapies — and it’s not a huge effect, that’s easily apparent early on — you’re much better [off] to randomize and get the right answer.

00:29:36:05 – 00:30:04:00

Rob Califf

And we could easily demonstrate [that]. Because I would say a fellow every day came in with some analysis. Most of them, half of them were wrong. But you couldn’t tell which half. And there was no fancy way to figure it out. Randomization was a much, much better approach. But that evolved in this ability to see patients, and collect data, and do the clinical trials.

00:30:04:02 – 00:30:21:06

Rob Califf

I think [it] is a part of medicine that unfortunately is under assault right now, and never really caught on. Because most people didn’t have the sort of institutional support that we had as all this started up.

00:30:21:08 – 00:30:35:14

Adrian Hernandez

So it sounds like you were really combining what you were seeing clinically, with actually generating new data about what to do, with your colleagues. And also, during the clinical trials, [you] would have more definitive answers.

00:30:35:16 – 00:30:59:04

Rob Califf

Yeah. I mean, what an amazing thing that one week you can be treating a group of people with a problem. You don’t really know what the right treatment is. The next week, you’ve gotten the answer in a randomized trial. And you go to talk to that person on the phone and you say, “We’re going to do this because we did a trial and it’s a better treatment. You have a much better chance of being alive, or being functional.”

00:30:59:06 – 00:31:19:19

Rob Califf

And to be able to do that in real time. It’s something that, given where we are with technology today, and given the 8 billion people in the world, this is the way we should be doing everything. But we’re a long way from it. In fact, I think one of the first few papers I wrote was predicting that we’d be doing this within five years.

00:31:19:19 – 00:31:21:23

Rob Califf

That was 1980.

00:31:22:05 – 00:31:49:22

Rob Califf

And of course, as you well know, Adrian, this is not a technology problem now. It’s really a cultural problem [in] that it’s hard for us to admit we don’t know the right treatment. And very often we don’t. And it’s hard for people to work together to agree on how to answer a question. Everybody wants to have their own — there’s a tendency for people to want to have their own predominance over the domain that they’re working in.

00:31:50:01 – 00:32:00:17

Adrian Hernandez

Yeah, it sounds like some of the themes around clinical science, but there is actually this social science and psychological science in terms of different biases that come together.

00:32:00:20 – 00:32:21:14

Rob Califf

Yeah, it’s all involved. And people forget that in those early days of treating acute heart attacks, we came up with some amazing [advancements] — your risk of being dead now is half of what it was then. But most things we tried didn’t work. What a humbling experience that is. When you have something you were sure was going to work,

00:32:21:16 – 00:32:45:10

Rob Califf

it worked in pre-clinical and animal models, and now you do the trial in human beings, and it doesn’t work. Or it in some cases even caused harm. It was not predictable until you did the study. Very humbling. But an experience I think more people should have so that they’re driven to want to get the answers, as opposed to presuming they know the answers already.

00:32:45:12 – 00:32:53:04

Adrian Hernandez

So when did you transition from doing the small trials with your friends and colleagues to something bigger?

00:32:53:06 – 00:33:28:07

Rob Califf

Well, it’s a small world. And, Ralph Snyderman had been a rheumatologist at Duke, and he had been recruited away to Genentech, the first really major biotech company in the world, out in San Francisco. [It was] started by many of our mutual professors at UCSF. And we were doing these small heart attack trials. And there was a new drug called tissue plasminogen activator [tPA] that Genentech developed.

00:33:28:09 – 00:33:55:05

Rob Califf

And the Europeans were doing large trials at the time. They did a mega trial. And lo and behold, the very inexpensive drug streptokinase was just as good as the highly-expensive American biotech drug tPA, as it was called. But they had dosed the tPA in a way we knew was suboptimal. And so there needed to be another large trial to answer the question.

00:33:55:07 – 00:34:20:22

Rob Califf

As it turned out, there had never been a US-based mega trial, as we call it. But Genentech was under investigation for bad marketing practices, and so they decided they needed to outsource the big mega trial to an academic center. And we’d gained the trust of both the FDA and the industry in our previous work.

00:34:21:00 – 00:34:34:10

Rob Califf

And so, they came to us and said, “Would you coordinate this trial?” I still remember we did a little sample size calculation. It came out that 30,000 people would be needed. Biggest trial we’d ever done before then was about 700 patients.

00:34:35:16 – 00:34:48:04

Rob Califf

And we’d never worked internationally. So, then some other things happened. We needed to add a fourth arm, and that increased the sample size to 40,000.

00:34:48:06 – 00:34:51:03

Adrian Hernandez

Did anyone say that you all were completely crazy?

00:34:51:03 – 00:35:18:08

Rob Califf

Most of the people that I was working with at Duke said we were completely crazy. And there were many stressful and tearful moments, just because of the — this was heavily-watched by the world because it really was, for people that follow the way the press works, it was a clash of the new biotech versus the old way of doing things.

00:35:18:10 – 00:35:45:14

Rob Califf

So we were constantly under scrutiny. But the trial got done in record time. And Ralph had come back to Duke, which created a conflict, interestingly enough. Much like many of the things that you deal with now. But [William] Bill Donelan, who was Ralph’s right-hand person and ran a lot of the operations, did a phenomenal job of brokering the kind of contract that now you take for granted.

00:35:45:14 – 00:36:15:15

Rob Califf

But it was a very new thing in academia to work this way with industry. And we got the trial done ahead of time. Got an answer. And it was, you know, a small difference. 1 in 100 patients saved with the new drug compared to the old. But that created an entire infrastructure for doing clinical trials that we then used over and over.

00:36:15:17 – 00:36:20:12

Adrian Hernandez

And was that the start of the DCRI [Duke Clinical Research Institute]?

00:36:20:14 – 00:36:50:01

Rob Califf

Well, once we had done that and a few other trials, it struck me that this was the method that needed to be used throughout medicine. And again, I had a lot of support from the institution, and the thought that we should create an entity that evolved from the database with a few clinical trials to an institutional entity that could be used by any specialty or primary care within the institution.

00:36:50:03 – 00:37:15:23

Rob Califf

And that was what led to the DCRI. It turned out that McKinsey was being run by people who were Duke grads. So we got a special deal for getting the world’s premier consulting firm to come in and help us put the structure together. Because there’s nothing that really existed like it at the time.

00:37:15:23 – 00:37:41:03

Rob Califf

And, as I like to say, we taught I think it was ten young McKinsey startup people all about clinical trials. They all went on and did great things, of course, in the rest of their consulting business. And we had an entity that could serve the faculty at Duke and their desire to get clinical studies done.

00:37:41:05 – 00:37:52:11

Adrian Hernandez

So you founded the Duke Clinical Research Institute in 1996 and had a ten year run at it. And what were the key things that happened during that time?

00:37:52:13 – 00:38:17:13

Rob Califf

Well, we learned a lot about the methodology of clinical trials. We answered a lot of questions that made a difference. We changed the way a lot of things were done in terms of people working together. But it also created a lot of interesting, complex situations within the institution and with the “outside world” people.

00:38:17:15 – 00:38:44:00

Rob Califf

[People] imitated us, or tried to take what we had done and do it better. So competition evolved. But, the very issue of being able to answer questions quickly was disruptive to people who were comfortable in the old way of saying, “I’m a professor, so I know the answer.” And that led to some issues. We also had some difficulty getting acceptance.

00:38:44:03 – 00:39:04:14

Rob Califf

Clinical research was an academic pursuit. Academia was dominated by the basic sciences at a place like Duke, and it was just not seen as being of the same stature as discovery academic research.

00:39:04:16 – 00:39:20:21

Adrian Hernandez

Now, you could have obviously chosen to build the DCRI outside of Duke. There are many examples of that in the industry. You chose not to do that. What was the reason for that?

00:39:20:23 – 00:39:45:20

Rob Califf

Well, it goes back to what I said before. I was completely stimulated by the view that the best way to do healthcare research was to do it in the practice of medicine. That is, I never thought of clinical trials or observational studies as some separate thing called research. It was really just a way of learning about how to get it right

00:39:45:20 – 00:40:10:14

Rob Califf

when you treated patients. And I was, at that point, very focused on clinical care [for] people who were sick. That was enough at the time to focus on. There was plenty to work on. So it really never crossed my mind, until we ran into some obstacles and difficulties with the university, that I should even think about

00:40:10:16 – 00:40:13:03

Rob Califf

taking it outside.

Adrian Hernandez

So,

00:41:13:11 – 00:41:23:19

Adrian Hernandez

DCRI isn’t just about cardiology, or wasn’t, even though you’re a cardiologist. Was that something intentional to be around different areas?

00:41:23:19 – 00:41:47:17

Rob Califf

It seemed to me that the methods we had developed were not just applicable to cardiology. They could help any specialty or any problem. And some people gravitated to it right away, and thought it was great. And some people found it to be disruptive to the sort of mantra [of] “I’m the professor. I know the answer.

00:41:47:19 – 00:42:13:10

Rob Califf

Why are you even asking the question?” And from my perspective, you never really know until you’ve really addressed the question in an empirical way, whether you’re right about your suppositions. So there was a variety of uptake of it, but I always thought it would be best for every part of the Medical Center to be answering questions about practice.

00:42:13:12 – 00:42:34:03

Adrian Hernandez

Now you had other roles at Duke. You were also the founder of the Duke Translational Medicine Institute and also [held] various vice chancellor roles over time. What were the key things there that you focused on?

00:42:34:05 – 00:42:59:11

Rob Califf

Well, first let me say that, there were many obstacles in getting clinical research accepted as a valid academic activity, but the battles were won. And I think it’s a characteristic of Duke as an institution that you’re put to the test, but it’s such an optimistic place that new things come along, they get accepted, and they move along.

00:44:29:06 – 00:44:44:15

Adrian Hernandez

So you led the DCRI for ten years, and then you went on to do some other roles, including founding the Duke Translational Medicine Institute. What was the background for that and what was going on nationally?

00:44:44:17 – 00:45:16:00

Rob Califf

Well, there was a lot of turmoil at the NIH as the DCRI evolved, and other institutions were moving into hardcore clinical research as a discipline. There was a view of a lot of people that the NIH was not funding enough clinical research, that it was too heavily [and] purely focused on discovery research. And there was a lot of concern that these discoveries were not being translated into interventions that help health, help human health.

00:45:16:02 – 00:45:17:16

Rob Califf

And so, we

00:45:19:13 – 00:45:50:00

Rob Califf

spent a lot of time at the NIH and had developed a program called the Clinical Translational Science Awards. I was very involved in that. And they were big institutional awards meant to build the infrastructure to help institutions go from the scientists in the lab with the discovery, to the steps that need to be taken to the cross chasm, as it’s called, between early science and a product that could be used like a drug or a device.

00:45:50:02 – 00:46:18:19

Rob Califf

And so we got one of the first grants, the first batch of grants, to do that. And that led to the [Duke] Translational Medicine Institute. And it was an amazing experience because it brought in a big tranche of money to take a lot of people who either had not thought about translating their findings into useful health technologies, or people who had wanted to do it but just didn’t have a way of making it happen.

00:46:18:19 – 00:46:28:02

Rob Califf

So sort of like this upstart of the DCRI, this was a very exciting time of new things getting done.

00:46:28:04 – 00:46:43:10

Adrian Hernandez

And along the years you were an advisor to the NIH, the FDA, other agencies. You eventually went to the FDA. So, what attracted you to go there?

00:46:43:12 – 00:47:05:18

Rob Califf

Well, it actually goes back to the big GUSTO trial, the first mega trial that we did. We upset a lot of people because we were using methods that hadn’t been used before. And some very forward thinking people at FDA encouraged us to do it, because they wanted to get the answer to the question. And I worked very closely with them.

00:47:05:20 – 00:47:37:07

Rob Califf

But it upset so many people that we went through a two-year congressional investigation. People accused us of, I don’t know, making up data or something. And so our data ended up being analyzed by multiple government agencies and outside consultants. Everybody got the same answer. The trial carried the day. But in the process of doing that, I became very good friends with people at FDA, and came to understand deeply the role the FDA plays in medicine and healthcare.

00:47:37:09 – 00:48:04:04

Rob Califf

And because of that, it turned out — I was interviewed twice for commissioner, and, you know, didn’t get the job. But finally the time came, when Peggy Hamburg who was the commissioner under Obama came and visited me, and said, “I’m getting ready to step down. Maybe you should be the next commissioner.

00:48:04:04 – 00:48:32:13

Rob Califf

But there’s a problem; he president has to ask you. But we have this job to be deputy commissioner.” At that point I felt like I had pretty much done what I was born to do at Duke. Turns out that wasn’t true. And I had people like you and [Robert] Bob Harrington, Eric Peterson, and Leslie Curtis as leaders who were doing a great job with what I felt like I started.

00:48:32:15 – 00:48:58:07

Rob Califf

So I went to FDA as a civil servant, which was an amazing experience. And I still — you know, while I was opposed to the Vietnam War, I had deep respect for my friends who volunteered or were drafted. Turns out my draft number was over 300. So I was in the draft. I was just not called in the draft. So I’d never done public service.

00:48:58:07 – 00:49:29:01

Rob Califf

And what an amazing experience to have such a clarity of mission about the public health. And after a few months of doing that, people were knocking on my door saying, “When is the president going to ask you to be commissioner?” And finally I was asked to brief President Obama, with 12 hours notice, on the error rates of gene sequencing. Which in 2016 was a relatively new..

00:49:29:01 – 00:49:29:18

Adrian Hernandez

Yeah.

00:49:29:20 – 00:49:57:14

Rob Califf

Topic. I went to the Roosevelt Room, right there next to the Oval Office [and] did my briefing. The room was full of people like Francis Collins, who was the NIH director. And I was amazed because, President Obama always read everything the night before. We didn’t even talk about the slides that I had prepared. He was right into the next level of questions, and very interested in the mathematics involved in this.

00:49:57:15 – 00:50:13:05

Rob Califf

And so as I was walking out, they said, “You’ve been asked to come to the Oval Office [tomorrow]. And [I] met with President Obama. Adrian, you’ve heard this story, but we had 30 minutes of a one-on-one. The first 15 minutes were UNC versus Duke basketball?

00:50:14:04 – 00:50:16:19

Rob Califf

He’s an enormous UNC fan.

00:50:16:19 – 00:50:19:06

Adrian Hernandez [laughing]

It’s one of his faults.

00:50:19:08 – 00:50:42:01

Rob Califf

He had this spat with Reggie Love, who was his assistant. We eventually got over that, and he asked me to be commissioner. So that was how that happened. But I still go back to those months as a civil servant. I learned a lot about how the government works, and what the value is of civil servants.

00:50:42:02 – 00:50:50:01

Adrian Hernandez

And was there anything that prepared you for your time at the FDA from Duke or your history?

00:50:50:03 – 00:51:14:05

Rob Califf

I feel like I’ve been so lucky because most of the things I’ve done have been an evolution, but not because I planned it out that way. I just had all those interactions with FDA because of what I was doing at Duke. And being an administrator in an academic center is very similar to FDA. At a place like Duke you have departments.

00:51:14:05 – 00:51:40:11

Rob Califf

They are all traditional stovepipe units. They have rivalries. You have centers and institutes that kind of cross. And you have deans. There’s always a rivalry between the dean and the departments, [the question of] who’s really in charge. At the FDA, you have centers that are commodity-based. Drugs, devices, biologics, food, cosmetics, animals — The Center for Veterinary Medicine.

00:51:40:13 – 00:52:05:22

Rob Califf

And the commissioner is more like a dean than anything else. Of course, there’s a huge role in public-facing and Congress-facing, but the internal workings at the FDA have all the same dynamics of getting along across people who have a — like, there’s one Duke. That’s one thing. There’s one FDA. But there are also components that have their own interests that have to be brought together.

00:52:06:00 – 00:52:19:02

Adrian Hernandez

And during your time at FDA, you spent two tours at FDA. You’re on your second tour here. What have been the most challenging problems you’ve faced?

00:52:19:04 – 00:52:45:17

Rob Califf

I’d say the first time through, I didn’t feel like there were terribly challenging problems. It became challenging when the election had an unexpected result, and I was out of a job much more quickly than I expected. But when I came back the second time, of course, having been through it once I had a pretty clear focus on what I wanted to accomplish.

00:52:45:17 – 00:53:19:14

Rob Califf

But one characteristic of being FDA commissioner is you get a new crisis every day. Often something you didn’t anticipate. So in this case the big infant formula recall, when the Abbott plant was unsanitary, happened the day I was confirmed. So immediately I was thrown into really dealing with food, more than anything else. And, I don’t know if things happen for a reason, but it turned out the food part of the FDA needed a lot of help.

00:53:19:14 – 00:53:47:03

Rob Califf

And we’re currently undergoing the biggest reorganization in the history of the FDA. It actually starts in operation the first of October. That’s been major. And there’s so many things about food. But it gets back to what I see as one of the two or three central overarching challenges. We’re in a country that’s far and away the wealthiest, with the most highly-educated people in the world.

00:53:47:05 – 00:54:11:05

Rob Califf

We have the worst life expectancy of any high-income country now. And it’s getting worse, not better, relative to other countries. So when I look at it from the FDA perch, we are also creating the innovations for the rest of the world. Far and away, everywhere I go, everyone agrees the U.S. is a source of creativity and new technologies and products, but there’s something wrong with what happens after that.

00:54:11:05 – 00:54:48:15

Rob Califf

So we get back to the old translation thing. And some of it is very rudimentary fundamental stuff, like why do we have this tremendous advertising machine advertising unhealthy foods when we know that nutrition should be different? Tobaccos, combustible tobacco, is still the leading remediable cause of death in the United States. Most people don’t realize that because most people like us, who are in the rarified university-type environment, nobody uses combustible tobacco here.

00:54:48:15 – 00:55:33:23

Rob Califf

But we’ve got 30 million Americans still using it. And we’re the only high-income country without graphic warnings on the cigarette package to remind people not to do it. So this is problem number one. And sort of related is the misinformation avalanche, which is overwhelming and getting worse, and very hard to deal with. And, of course, the other thing that happened [is] I came back in the middle of the peak of the pandemic. And that was extremely challenging, because the FDA had to do its pandemic work and all of its other work with the same people in a virtual environment.

00:55:33:23 – 00:55:38:04

Rob Califf

So big challenges, but also interesting.

00:55:38:06 – 00:55:45:15

Adrian Hernandez

So, your tour is not over yet. What’s one of your proudest moments at the FDA so far?

00:55:45:17 – 00:56:07:16

Rob Califf

To me, the most important thing about the FDA is the value of civil service. So I’m very proud of the people that work there. You come to work at the FDA knowing you’re going to get criticized at everything that you do. There’s an analogy to working in an intensive care unit. You have to make decisions.

00:56:07:18 – 00:56:30:11

Rob Califf

Even if you have imperfect information. You can’t say, “Well, I’m sorry, you’re in cardiac arrest, come back next year when I have an answer as to what to do.” You’ve got to do what you think is best. And very often there are timelines on things where FDA has to make a decision with imperfect information. Almost every decision, because we’re regulating 20% of the economy.

00:56:30:13 – 00:56:55:13

Rob Califf

So the difference is you’re dealing with families in the intensive care unit, and sometimes hypercritical interns and residents, etc. But here you’re dealing with the national press [and] the Congress. And the second-guessing is extreme. But through it all, civil servants have a mission. It’s a tremendous workforce. I’d highly recommend that people read Michael Lewis’

00:56:55:14 – 00:56:59:11

Rob Califf

But The Fifth [Risk], especially pertinent to the..

00:56:59:11 – 00:57:01:13

Adrian Hernandez

I’ve read it, and I understand what you mean.

00:57:01:15 – 00:57:13:11

Rob Califf

So it’s all about civil servants. He’s doing a series in the Washington Post right now where he’s picking a civil servant every week, and they do the whole, “people you’ve never heard of that do [important] things.” [crosstalk]

00:57:13:16 – 00:57:14:04

Adrian Hernandez

Yeah.

00:57:14:06 – 00:57:36:15

Rob Califf

But he also has a podcast [episode] called Ref, You Suck! Which I highly recommend. It’s very pertinent to FDA, and it’s about what’s happened in our society where — and I think the FDA largely is a referee because contrary to what a lot of people think, the FDA doesn’t write the rules. The rules are written by Congress. They’re called laws.

00:57:36:17 – 00:58:03:05

Rob Califf

But then there’s a rule book, which the FDA contributes to, that’s agreed to. And then when other products get on the market and what happens is adjudicated according to the rule book. There’s something that’s happened in our society. We’re criticizing the referees as a national pastime. What’s also interesting about it, as he points out, it used to be that the worst players criticize the referees.

00:58:03:07 – 00:58:30:10

Rob Califf

Now if you think about it, it’s the highest paid, most talented players who are most likely to criticize the referees. And I think very much in the power struggle of corporations and products, we get a lot of powerful criticism, but it comes back to the FDA employees [who] put their heads down and do their work. And it’s really an amazing thing to see.

00:58:30:12 – 00:58:40:19

Adrian Hernandez

Now we’re here celebrating Duke’s 100 years. So what do you think Duke needs to be doing to prepare for the next 100 years?

00:58:40:21 – 00:59:07:01

Rob Califf

Well, the Centennial Founder’s Celebration was last night, and I had a lot of chance to reflect on it and heard an amazing session, which I hope is going to be all over YouTube from the three former living [Duke] presidents – Nan Keohane, Dick Brodhead, and of course, Vince Price. And questions by Judy Woodruff.

00:59:07:01 – 00:59:29:22

Rob Califf

So they were not softball questions. But I think the most important thing for Duke to do is actually look at its history. Of course, I have a particular view on this being from South Carolina, coming the furthest north I’d ever been to come to Duke. The sort of thing ringing in my head is Duke is where the history of the South meets the changing current conditions.

00:59:30:00 – 01:00:01:19

Rob Califf

And that was definitely true in the late 1960s. If you look at society today, we have this terrible problem with our health. We have a fundamental disrespect for [and] loss of confidence in institutions like universities. They talked last night about the bubble. If you go to a place like Duke, and then you go and live in San Francisco or Washington or New York or anywhere, live in a suburb with people who went to similar institutions.

01:00:01:21 – 01:00:28:15

Rob Califf

It leads to a division in our society, which is very detrimental. And, we used to call him Uncle Terry. But if you look at Terry Sanford, I think everyone agreed. Like, here’s a person, he wasn’t perfect, but he had a sense of what the average person in North Carolina was going through. And he had a view that universities were critical, but he did it in a way that actually brought people in and didn’t alienate them.

01:00:28:17 – 01:00:52:10

Rob Califf

I would also say we had university leaders over time who had courage. Courage to tackle racism, courage to tackle sex and gender inequality. Nan Keohane made the point that the Women’s Campus was actually thought of as kind of a weird thing, but it was a great asset because women at Duke had status from the beginning.

01:00:52:10 – 01:01:17:22

Rob Califf

But she put into place same-sex marriage at the Chapel in the year when the Methodist Church made a pronouncement it was not going to support same-sex marriage. And that took courage. On the medical side, we had people who started helicopter programs that were thought to be financial losers, to save lives. We had [Barton] Bart Haynes who tackled HIV

01:01:17:22 – 01:01:53:19

Rob Califf

when you weren’t allowed to use the word AIDS at Duke because it brought up these concerns about homosexuality or gay behavior, as it was called at the time. Bart took it on, and did amazing research at the [Duke Human] Vaccine Institute. I told the story last night, one of my freshman dormmates used to say, if you come to Duke, you get free tickets. And he was from Hickory, North Carolina.

01:01:53:21 – 01:02:16:23

Rob Califf

We’re a wealthy institution, relatively speaking, and we get free tickets. Our leaders historically have used those free tickets to do things that you couldn’t do at other places. There’s another option, which is to say we’ve got a lot of money, let’s rest on our laurels. Let’s protect ourselves from the risk of doing new things. This is not a time to be complacent.

01:02:17:03 – 01:02:42:05

Rob Califf

We are in serious trouble in this society, both on the health side and on the side of the pursuit of truth. There is also a great quote in the video that’s being used for the Centennial from [William Preston] Few, the original president, that basically said something to the effect of “I want to create a shining place which pursues truth for the good of our fellow human beings.”

01:02:42:07 – 01:02:54:02

Rob Califf

So, here we are in a world of misinformation. What a great time for leaders to step forward, even if they’re going to get criticized, and [to] make a difference.

01:02:54:06 – 01:03:10:07

Adrian Hernandez

So it sounds like a key word here is courage. Courage to do the right thing. Courage to do something different. Courage to actually lean in and have some views of how other people are living.

01:03:10:09 – 01:03:28:10

Rob Califf

That’s right. And I keep going back to Dr. Stead because he was such a mentor to me. And, you know, he was an unusual person. People thought of him as unusual. He came up with a lot of ideas that didn’t work out, but who else would have thought of a physician’s assistant program?

01:03:28:10 – 01:03:52:15

Rob Califf

And here we are, try to get a primary care appointment today. He saw that coming, and didn’t completely get the job done, but it certainly built a bridge, which is, I think, a segue into the future. And using computers in medicine when other people were afraid of computers at the time.

01:03:52:15 – 01:04:05:11

Rob Califf

So, I think courage and I think part of the American way is to try new things. Some of them don’t work. That’s okay. Take the criticism and keep going.

01:04:05:13 – 01:04:19:17

Adrian Hernandez

And final one, last question. [Robert] Bob Lefkowitz, Nobel Laureate at Duke, often comments, “It’s better to be lucky than not.” Do you feel like you’ve been lucky over the years?

01:04:19:19 – 01:04:54:18

Rob Califf

I have definitely been lucky. Nothing that happened in my career was really, sort of [where] I thought about a long time, planned it all out over the course of years. Things just happen. But I do think the old motto is, “Luck is where preparation meets inspiration.” I think there’s a lot to that. And hopefully even as I’m turning 73 this year, I’ve still got an open mind.

01:04:54:20 – 01:05:29:00

Rob Califf

There’s some amazing things happening. Of course in my job at FDA, I get to see 20% of the economy. All the new things that people are thinking about and doing. So I’ve definitely been lucky. And been lucky to be in an institution that has its warts. It’s not perfect. But it has over the years supported people who did new things that were different, and that other people weren’t yet trying.

01:05:29:00 – 01:05:38:09

Adrian Hernandez

Rob, thanks for spending time with us. Sharing your past history before Duke, at Duke, and now at FDA.

01:05:38:11 – 01:05:40:13

Rob Califf

Thanks, Adrian. Good to be with you.