They are known simply as “The First Five.”

Sixty years ago, Mary Mitchell Harris, Gene Kendall, Cassandra Smith Rush, Nathaniel White and Wilhelmina Reuben-Cooke made history when they crossed Duke’s academic color line in 1963 and became the first African Americans to integrate the school’s undergraduate program.

Duke was one of the last major universities in the South to desegregate. Change began on March 8, 1961, when Duke’s Board of Trustees voted to desegregate the university’s graduate and professional schools.

Although not every member of the First Five earned an undergraduate degree from Duke, they all went on to contribute as leaders in the military, education, law and activism.

Mitchell was an honors student at Durham’s historically Black Hillside High School. She knew by 10th grade that she wanted to attend Duke.

Kendall decided to enroll at Duke and major in electrical engineering when the school offered him a full scholarship.

Rush was a zoology major twice-denied admission before the university desegregated.

White grew up less than three miles from campus but declared enrolling at Duke was “like going to a whole new city.”

Reuben-Cooke, who has a building on Duke’s West Campus named after her, first hesitated to attend Duke because her father was enrolled at the Divinity School, and she was worried he would keep too close an eye on her.

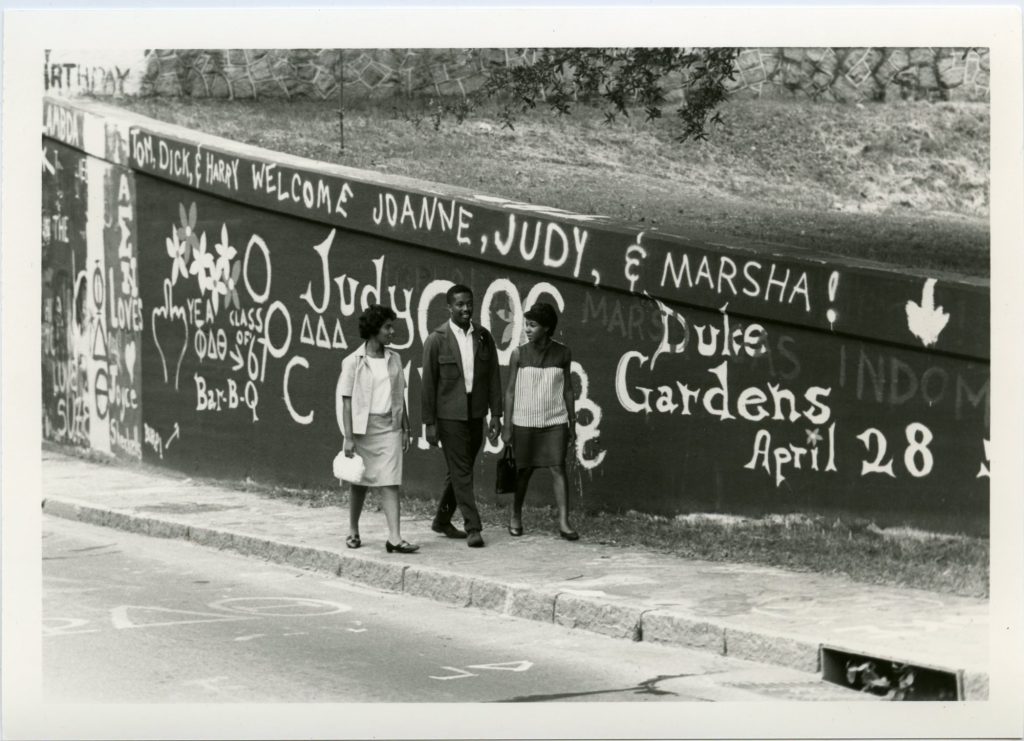

When the First Five enrolled for classes, Duke was a far cry from being a bastion of diversity and inclusion. The young students discovered a university with no Black faculty members, administrators or trustees. They “encountered culture shock as they forever changed the fabric of the university,” said a school website celebrating the 50th anniversary of the First Five.

Today, inclusion — “to fully engage people of diverse backgrounds, abilities and perspectives” — is one of Duke’s core values.