In 1936, a 22-month-old baby fell into a river in Canton, North Carolina, and drowned. After using dynamite to dislodge the river bottom, officials sent what they thought were the little boy’s remains to Duke University, where pathologist Dr. Wiley Forbus prepared his microscope. However, after careful examination, he determined “the specimen was from some species of fish.”

Forbus specialized in answering the questions of survivors. He was a pioneer of forensic pathology and a leader in visualizing scientific information. The Canton investigation was just one part of a public outreach program Forbus created to use Duke’s scientific facilities to help a network of North Carolina communities. Because of him, instead of burying a fish, the search for the child continued.

After returning from WWI, where he was an artillery spotter for the U.S. Army, Forbus enrolled in medical school at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

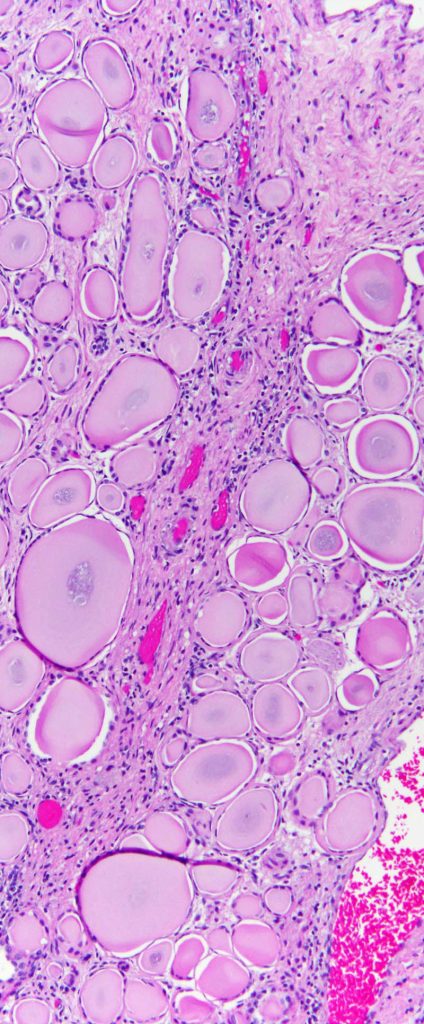

He gravitated toward pathology, studying tissues to understand disease and examining the dead to understand what killed them. At that time, pathologists struggled to communicate adequate descriptions of abnormal anatomies because cameras were not yet ubiquitous. The cameras of the era were clunky, wood-framed, accordion-like contraptions, and most pathologists relied instead on text and hand drawings to describe their findings to another physician. Pathology slides were (and are) wafer-thin slices of tissue mounted onto fragile glass slips to inspect the smallest details of cells in cross-section under a microscope. Before photomicroscopy, a pathologist would need to describe the imagery with words, sketch hundreds of cells by hand, or ship the delicate slides in the mail. If they shattered, a sample and its insights would be lost forever.

Forbus was one of the early pioneers to see the potential of scientific photography, especially for communicating about disease states that could not be seen with the naked eye.

He and a small number of other pathologists began bolting cameras to their microscopes. In these early acts of biomedical engineering, they designed and built stands to perch their accordion-box cameras above microscopes’ eyepieces. Eastman Kodak caught on to the practice and published instructions for how to make such an assembly. The photography company also issued guidance for reproducing the brilliant colors of stained tissues during a time of black and white film.

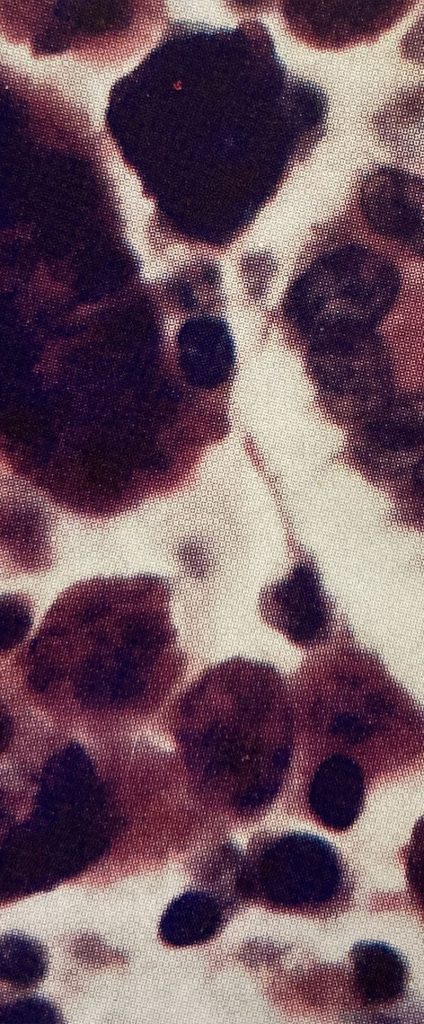

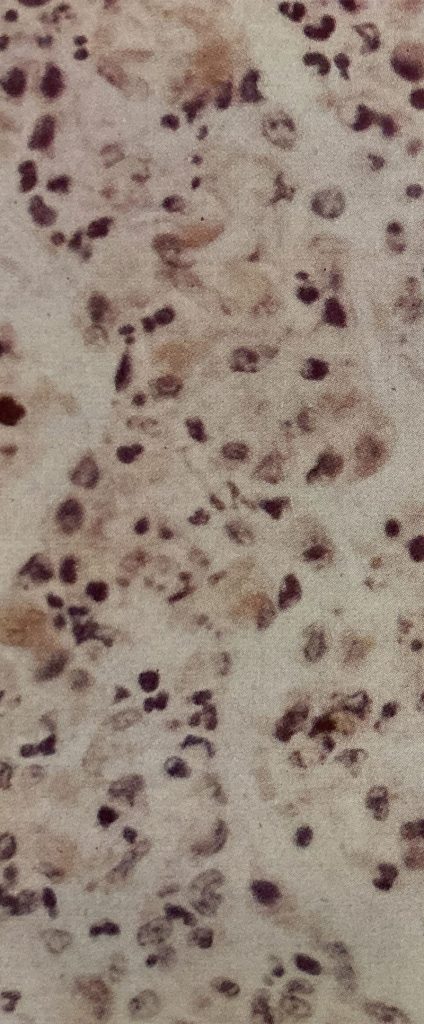

To make a color image, the pioneer photomicroscopists like Forbus could sequentially place two to three light-filtering films over the camera lens, take one image each time, then cast each image onto glass using a special kind of gelatin. This gelatin could be stained in red, green, or blue-violet; one color on each exposure plate. The multiple exposures were then overlaid to create a full-color picture.

The process was fiddly and exacting, and few could manage it, but Forbus was among them. He found this new visualization key to the study of disease.

“So much of pathology is in bright colors,” according to Dr. Marianne Hamel, the modern pathologist-photographer behind the microscopic-art Instagram account Death Under Glass. Hamel says Forbus was ahead of his time, by almost 100 years.

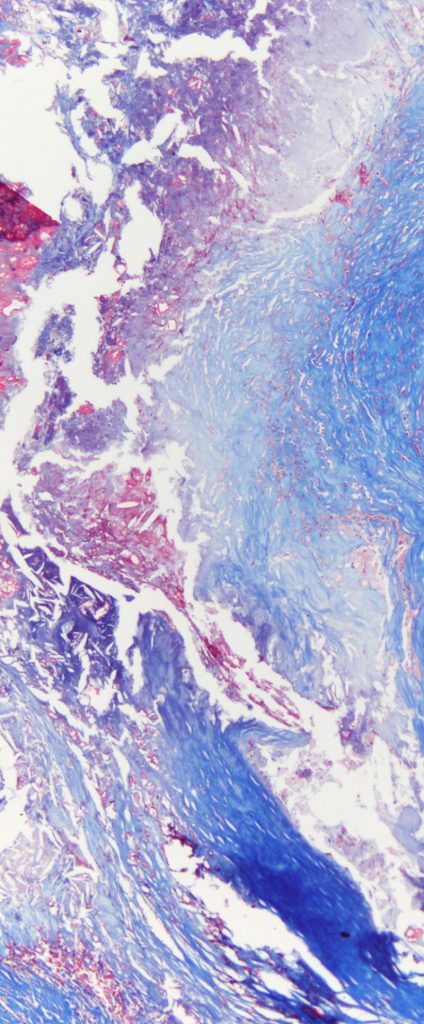

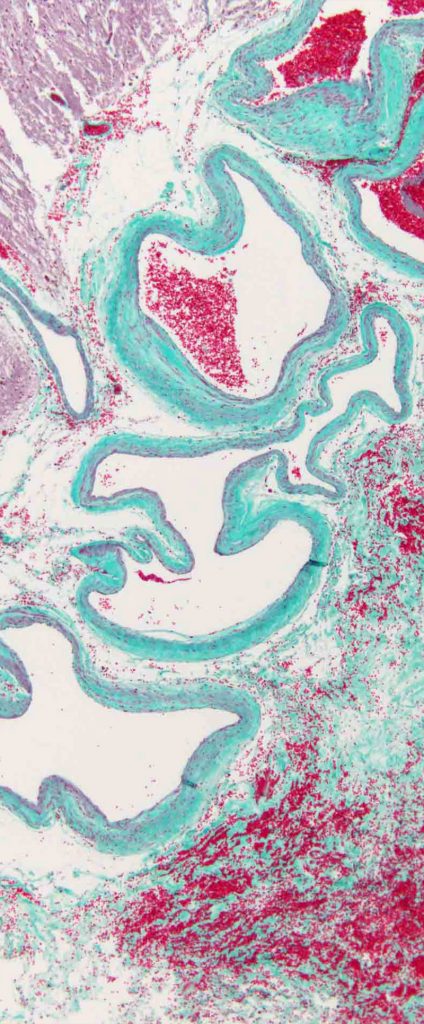

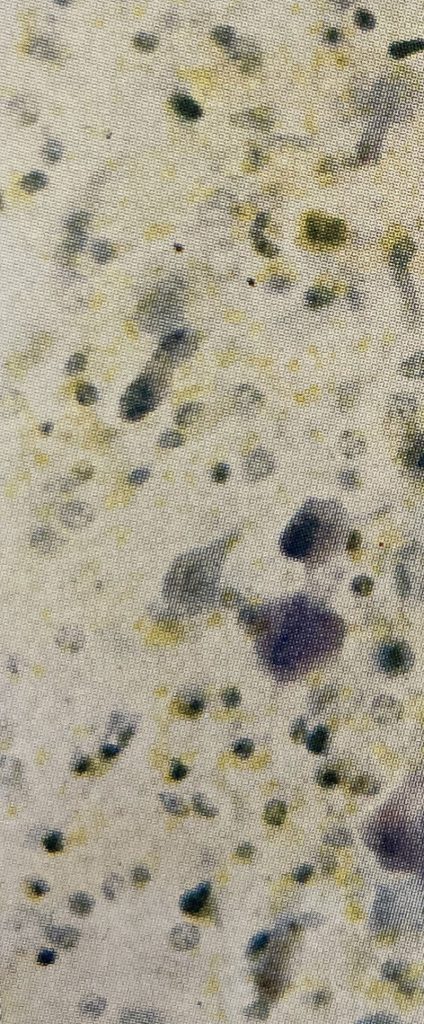

From left to right: Whipple’s Disease (Forbus, 1943), Pneumonia (Forbus, 1943), Thyroidization of the Kidney (Courtesy Marianne Hamel), Hardening of the Arteries (Courtesy Marianne Hamel), Arteriovenous Malformations (Courtesy Marianne Hamel) and Erythroblastosis Fetalis (Forbus, 1943)

His ideas paid dividends by launching Duke in the field of disease research.

When Forbus came to Durham as one of the earliest faculty recruited to Duke Hospital, he brought with him his Kodak pamphlets, his microscope, his box camera and his revolutionary ideas. He didn’t have a place to live yet because Duke was behind in constructing lodging for the first wave of faculty. But the administration begged him to understand “the whole plan is an experiment,” and pointed out that everyone was being inconvenienced together as a new university was being born.

Forbus agreed to come despite the inconveniences. He was flexible about having somewhere to live, but he insisted that Duke organize some artists and illustrators to help supplement his photography.

One of Forbus’s first projects was to coordinate with other local hospitals. He connected with Durham’s Watts Hospital and Lincoln Hospital to arrange for them to send not only deceased patients for autopsy, but samples from surgeries of living patients for better diagnostics. Better diagnoses meant better treatments.

Watts Hospital, whose buildings now serve as the North Carolina School of Science and Math, was established to provide philanthropic care for the impoverished white residents of Durham. Lincoln Hospital was the counterpart for the Black residents in the then-segregated South. Neither hospital could afford to employ their own pathologist, so Forbus’s program meant he was providing this type of diagnostic care to these populations for the first time. His photography meant he could send detailed information back to the hospitals’ treating physicians, and together the teams could compile more informed plans for treatment and prevention.

The first year of Forbus’s program, in a time before pathology was a recognized medical specialty, Duke’s pathology department was an informal group comprised of only him, two assistants, and a handful of student volunteers. They conducted the first autopsy at Duke on Aug. 5, 1930, and then experienced an immediate “constant demand for pathological work.” By the end of the year they’d performed 168 autopsies for Duke Hospital — 70 percent of the deaths — and inspected surgically removed tissues for 1,620 patients from Duke, Watts and Lincoln. Quickly, the little group was required to expand.

Forbus realized that scientific research was the way forward in this new field, and because of his team’s ability to preserve tissue slides and share the images, he was in a position to lead it. He and the pathology team had been doing research on their own time and with their own money, looking into the spread of tuberculosis in the community, designing new autopsy tables, and figuring out how to coordinate with law enforcement to contribute pathology techniques to the nascent field of forensic medicine.

Forbus brought those arguments to Duke’s leadership. He pointed out that Duke Hospital could be more successful in treating patients if their personnel also led the way in understanding diseases, telling the dean that one of their priorities had to be “the investigation of disease by planned sustained research.” Other faculty of the time agreed, buttressing Forbus’ case with statements like “no school can be considered anything but second class that does not cultivate a spirit of research in all its departments” and saying that research was the way “to increase the stature” of medical departments. Forbus wanted Duke to use its research to light the path toward better health.

The leadership saw his point and Forbus got his wish. To this day, thanks in part to Forbus’ advocacy, research remains a focus for Duke Health, including the School of Medicine’s unusual third year of training in research.

Forbus also wanted to spread the benefits of research to the outlying community, and make sure everyone’s medical issues were studied, not only those of the patients treated at Duke. His outreach dream started running at a financial deficit because many North Carolina hospitals that were smaller, more rural, or focused on charitable care, could not afford to pay the actual costs involved. However, the research resulted in such positive clinical outcomes that physicians from these hospitals asked how their patients could be included anyway. It seems Forbus always welcomed them.

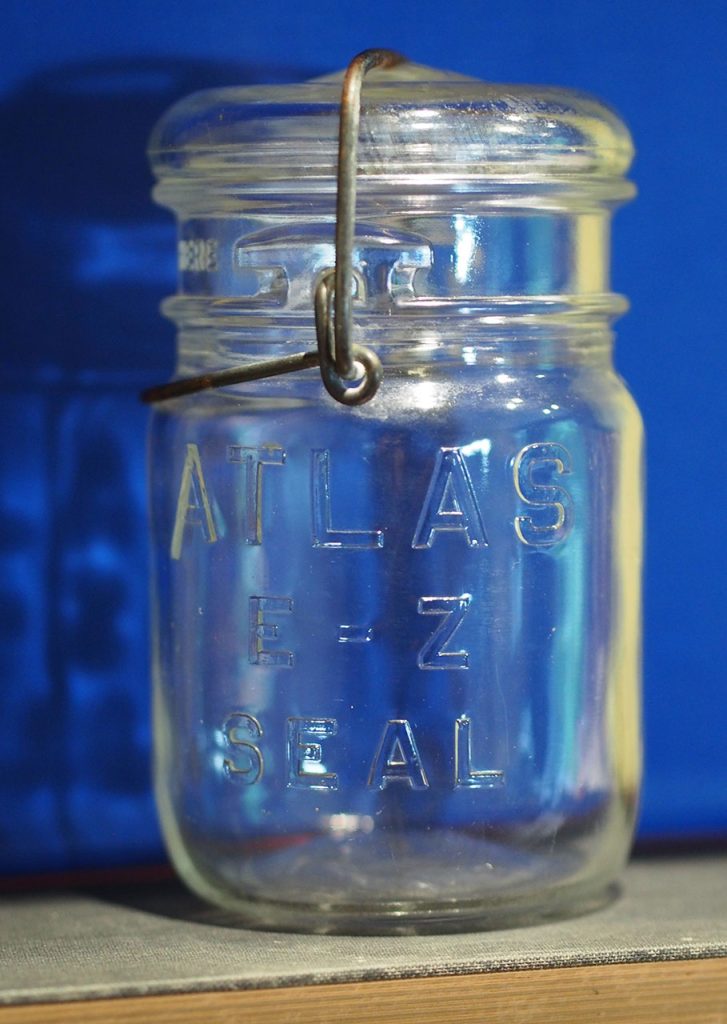

To help them with their diagnoses, Forbus sent strict instructions for preparing and mailing the organs to Durham using low-budget methods, including canning jars: “a very satisfactory glass container for shipping specimens is the Atlas one-half pint or smaller fruit jar,” he wrote. The Duke Endowment covered the costs the other hospitals couldn’t, which was about half the total expense.

In just three years, Forbus and his growing team had reviewed tissue from 4,554 surgical patients to better inform their treatments. They had completed 615 autopsies. They were working with 14 other hospitals, still at a financial deficit, but with great benefit to the North Carolina community.

The work was not without ethical complications. Our modern interpretation of patient consent continues to evolve, and as of this writing, it is still legal for physicians to use tissues harvested from their patients however the physicians wish, without patient consent, so long as the tissues were taken from the patients in the course of medical treatment. It is still common, therefore, for physicians and pathologists to preserve, retain and use for research, pieces of patients they found to be medically interesting. One of the ways Forbus was able to get Duke Endowment funding to provide these pathology services to impoverished white and Black communities was by advertising that “all materials (tissues) obtained from both the Watts Hospital and the Lincoln Hospital become the property of the department.” This practice is now undergoing some community review in light of what we’ve learned about Henrietta Lacks and the research legacy of other patients.

Soon, the growing pathology program and its ability to preserve results using photography expanded into the legal field. By 1933 the Durham city and county coroner brought “virtually all” their cases “to the laboratories for investigation.” Murder victims were sent to Duke so the pathologists could hunt for clues that could lead to their killers.

Forbus’ techniques of preservation enabled the cataloguing and study of diseases in a way that changed the field of pathology. His research papers stand out from others of the 1930s and 1940s because of their stunning images, which he often published in color using the labor-intensive multi-plate methods, 70 years before the birth of modern digital techniques. Forbus’ compilations of tissue images were heralded as “entirely new” and “masterly,” because of the way he sorted the images like large datasets, organized by disease type to allow comparing how diseases varied between people.

“Although the technology surrounding photomicroscopy has changed, the idea is the same,” says Hamel, the pathologist-photographer: “To capture and share images so that others can see ‘the pathologist’s view of the world,’ so to speak. Learning to read and interpret histological specimens is like learning another language entirely, and Dr. Forbus clearly recognized the critical role that pathologists play as the interlocutor between tissue and clinician.”