In the summer of 1941, just months before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Duke political science professor Paul Linebarger was on the ground in China with support from the Duke University Research Council.

The young Asian studies specialist was one of the few Western researchers with the language skills, cultural sensitivity and connections to access rural China and the country’s political leaders during the brutal, infamous Rape of Nanjing by invading Japanese forces.

Linebarger was able to bring insightful, accurate reports of the Japanese occupation to the English-speaking world and his understanding of the brewing war in the Pacific laid the foundation for many Americans’ understanding. Immediately after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Army pressed Linebarger into a crucial role as the leader of its psychological operations on behalf of China in the fight against Japan. After the war, Linebarger co-founded the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University and became a famous author of romance, suspense and science fiction under several pseudonyms. His books are still for sale on Amazon.

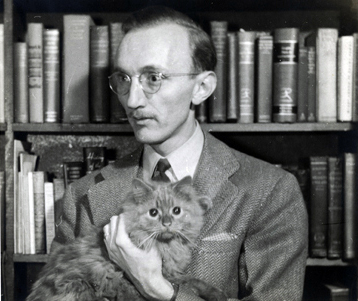

Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, born in Milwaukee in 1913, had a broad, crooked smile and large eyes capable of profound perception, despite their need for circular wireframe glasses. He was American by birth and German by heritage, and he used to say that he had learned Chinese before he learned English.

His father, also named Paul Linebarger, spoke 14 languages. He started his career as a judge in the Philippines before moving on to become legal adviser to Chinese political leader Sun Yat-Sen during the 1911 revolution that resulted in the overthrow of the 4,000-year-old Qing Dynasty.

Young Paul had a front-row seat to the aftermath of the overthrow as a child growing up in China. His parents had traveled back to the United States for his birth, but returned with him to China shortly afterwards, and there he witnessed the rebuilding from the revolution unfold. Likely as the result of growing up during this key life event, Linebarger developed a dislike for non-representative governments, and for any inklings of fascism or monarchy that would subvert the true will of a people.

In 1937, when the Japanese military attacked mainland China and began an inland march hallmarked by massacre, destruction and rape, Linebarger seems to have taken it personally.

Shortly before the Japanese invasion, the Soviet-affiliated Left Wing of Chinese politics had set a price on the head of the elder Paul Linebarger, who needed this bounty to be withdrawn before he could take a position as head of the Council of State for Chiang K’ai-Shek. Once the bounty was withdrawn and the Linebarger family’s safety was less obviously under threat, his now-adult son Paul accompanied him as a private assistant to the council of the prominent military leader. Their united goals, based on later writings from professor Linebarger, were to see how they could help solidify peace for the young government. With the death of his father in 1939, Linebarger would have to continue this work alone.

Paul Linebarger became a lecturer at Duke at age 24 after earning his doctorate in political science at Johns Hopkins, but he was quickly promoted to full professor in the political science department just one year later. He became well-known for his lectures on Chinese culture for those who wished to better understand the brewing conflict.

During one of these lectures, he encouraged female listeners with the insight that in China, women’s rights had expanded to the point that all jobs were open to women, a policy in sharp contrast with those of the United States.

While he was a young lecturer, Linebarger also met his wife, Genevieve Collins, who was a student at Duke. Genevieve Collins Linebarger earned a Ph.D. and went on to publish prolifically in her own right regarding her research on political science, and she supported and edited professor Linebarger’s work for the last 16 years of his career.

Duke’s research council had sent Linebarger to Nanjing and western China in the summer of 1941 to research the situation in more detail. In a resulting publication about what the world was then calling “the China Incident,” Linebarger came to the conclusion that “all the atrocity stories sent out thus far have been sharp understatements of the truth.”

His interviews with survivors of the Japanese invasion informed his book on the experience titled “The China of Chiang K’ai-Shek,” in which he published observations about the attempted Japanese rule, and the cultural and political differences that would make it a challenge to maintain.

Linebarger called the invasion what it was, despite living in a time period that had not yet eschewed colonialism. He wrote with derision that the invasion was “the old-fashioned idea of carving out a simple imperialist area for economic exploitation.” The Japanese army, he said, was working as an “unacknowledged colonial machinery.” Based on what he was seeing in the region, he culturally translated for the American audience that the Japanese media would be prone to downplay the atrocities committed in order to avoid discussing “the slaughter of innocent people for sheer conquest.”

Sadly, much of what Linebarger wrote and predicted from his 1941 research turned out to be accurate. The war crimes that were later confirmed in Nanjing and the other areas where Linebarger traveled for his Duke research are now considered well-established record.

Upon his return to the U.S. in fall 1941, Linebarger took charge of a fundraising effort to provide aid to rural China, especially the parts struggling economically from the invasion. He worked to deliver food and money to these regions, while advocating for public concern and American intervention to end the invasion.

Linebarger’s research at Duke reflects a deep, thoughtful insight into the mechanisms of the government of Chiang K’ai-Shek during a time of historic upheaval, yet he maintained the objective and skillful emotional neutrality of a professional scholar.

Notable for their absence from his writing are any words pejorative of the nationalities described, or any suggestions or implications that the cultures of China and Japan should be regarded as inferior to those White or Western. Indeed, one of the obituaries written after his death in 1966 stated “in the matter of origins and races, he made no distinctions,” an attitude of respect toward others that would likely still be considered notable now, and was much more so during his era.

Unfortunately, the prescient words of the father and son Linebarger regarding the military situation with Japan turned out to be true, but their warnings went unheeded until one infamous day in December of 1941.

Paul Linebarger Sr. had cautioned in a 1937 interview for the International News Service that “if the conflict continues, another war will perhaps come, a war which will make the last one (WWI) look like small potatoes indeed.” His son, professor Linebarger, had forecast that local Chinese culture would be resistant to further attempts at colonial rule, such that “nothing short of a massacre” could ensure the obedience of the local Chinese people to foreign rule. The Linebargers were right. The conflict continued to expand, and worsen.

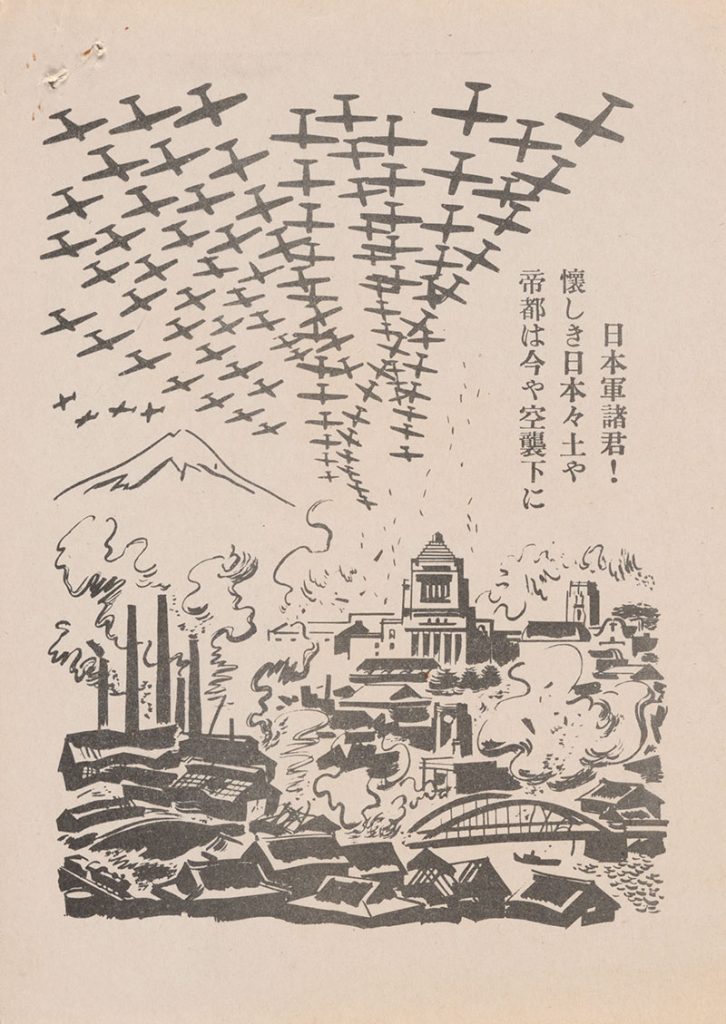

Shortly after the infamous Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. on Dec. 7, 1941, the U.S. Army commissioned professor Linebarger as a 2nd Lieutenant, and charged him with leading the psychological warfare operations for the Far East Division of the Office of War Information. His objective was to create propaganda to foil Japanese expansion in the Pacific, but more importantly to encourage the people in China to continue to resist the foreign rule of their homeland.

WWII propaganda leaflets from the files of Paul Linebarger and likely developed by him. These leaflets were intended for distribution to Japanese troops occupying China. source: (Stanford University Archives)

Linebarger was awarded a bronze star for his efforts, a physical ribbon that he referred to as “a reminder of a ruined and war-sick Chungking lurching blindly toward a victory with which it could not possibly cope.” He left the military as a major when the world war wound down, and was later recognized by the Chinese government with their own award of thanks.

Linebarger returned to Duke in late 1945, but was soon recruited to help establish the now-prestigious School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins, for which he was one of the four key founding professors. Linebarger wrote a seminal text on psychological warfare tactics based on his time with the military, and over the next two decades his writings on political science and military tactics continued to provide stunning insight into global events with preternatural accuracy.

He continued to write about the difference between “true peace” versus “false peace,” such as the Communist calls for peace that were really calls for their own world domination. He became president of the American Peace Society, and an obituary written by a colleague described his leadership style as a strong mentor to others who “wrote and spoke with speed but advised with patience.”

For fun, the prolific and natural linguist studied Spanish to add to his repertoire of fluent English, Chinese and German. He also wrote romance books under the pen name Felix C. Forrest, adventure and suspense novels under the name Carmichael Smith, and science fiction books that rose to high levels of popularity under the name Cordwainer Smith. His Cordwainer Smith novels are still the subject of research today for their intersection of Southern and Chinese thematic influence.

Paul Linebarger used his experiences conducting political research in western China to advocate for a form of peace that included governments based on true representation by the people, rather than dictatorships. He wrote in his final academic paper, which was published three years after his death, that “means create the ends, no matter what the rationalizations may say.”

It was a poetic summary of his career’s experience, a succinct way of saying that true peace can never come from force or massacre.

Paul Linebarger died of a heart attack at age 53 following several months of illness in 1966, but the research he conducted in post-invasion China under the aegis of Duke University’s Research Council is still considered the seminal work regarding that region and time period. Linebarger foreshadowed America’s conflict with Japan on the precipice of WWII and his book has been cited favorably by other researchers as recently as 2023.